Hossam Badrawi, a prominent physician and politician and former head of the OB/GYN department in Cairo University’s Medical School, reflects on how the hidden world inside us shapes our health, identity, and being.

Within the hushed corridors of the human gut, life thrives unseen. It is a vibrant, essential life — one without which our own could not persist.

Each human body hosts a vast and diverse universe of microorganisms: bacteria, fungi, viruses, and protozoa.

Together, they form the gut microbiome, a realm so teeming with activity that it outnumbers our own cells. Estimated at over 40 trillion microorganisms, this ecosystem performs functions vital to our existence: digesting fibre, synthesising vitamins, regulating the immune system, protecting the intestinal lining, and even producing neurochemicals such as serotonin—establishing what is now known as the gut–brain axis.

These beings are not invaders. They are cohabitants — more accurately, inhabitants.

They live in a delicate symbiosis, a biological contract grounded not in dominance but in balance. All they require is a stable inner climate, a nourishing diet, and moments of calm. In return, we gain vitality, resilience, and mind-body harmony.

Such a relationship forces us to reconsider the nature of our selfhood. Are we merely individuals, or are we composite beings—communities of “I” and “they” sharing a body, a journey, and a fate?

If these creatures think in chemical codes, regulate our mood and immunity, and live through us, are they not part of our expanded self?

This inner life opens a philosophical inquiry: What is the self?

Is it defined by our minds, our DNA — or should it include the silent multitude that breathes, digests, and works within us? In caring for them, are we not also caring for ourselves?

Thus, the art — and ethic—of tending to the inner climate emerges.

When this microbiome is thrown off balance through antibiotics, poor nutrition, or prolonged stress, the consequences ripple outward, affecting not just digestion but also mood, focus, immunity, and vulnerability to chronic illness.

So, how do we nurture this inner ecosystem?

• By consuming a diverse, fibre-rich diet: vegetables, fruits, and whole grains.

• By avoiding ultra-processed, sugar-laden foods that feed harmful microbes.

• By including probiotic-rich foods like yoghurt, kefir, and natural pickles.

• By cultivating emotional calm, knowing that stress disrupts microbial harmony.

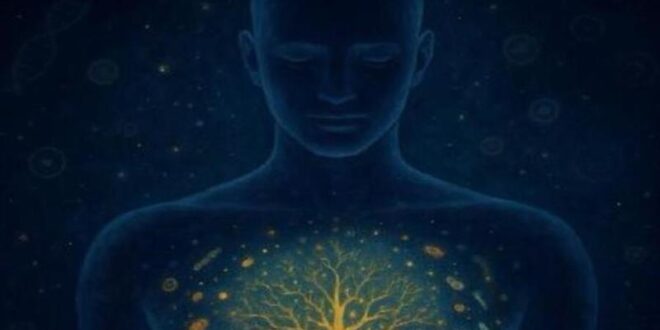

Now imagine — in a moment of inward vision — a transparent human figure standing in serene stillness, a statue of light. Within its abdomen spins not a digestive tract, but a galaxy of glowing particles, a cosmic spiral hidden in the belly.

Microbes swirl like golden and blue planets, orbiting in silent harmony — an invisible orchestra performing for the soul.

At the centre of this living galaxy grows a luminous tree. Its roots descend deep into the gut, while its branches rise through the chest and into the mind, bursting into thought sparks. It is as though thought begins in the earth within, not only in the head.

The image whispers:

“You are cosmically alive within, just as you are without. Whoever tends to their inner climate lives in balance — within the body, and with the world.”

We realise: we do not simply carry a hidden universe — we are that universe.

We are complex kingdoms, co-governed by ecosystems that sustain our vitality and meaning.

To live fully, one must befriend these inner inhabitants, respect the laws of their realm, and give them the balance they need, just as we honour the soil that feeds us.

They are not guests.

They are partners.

Perhaps they are the origin — and we, the echo.

In their silence is wisdom.

In their labour, life.

And in their presence, a secret of creation.

Dr. Hossam Badrawi Official Website

Dr. Hossam Badrawi Official Website